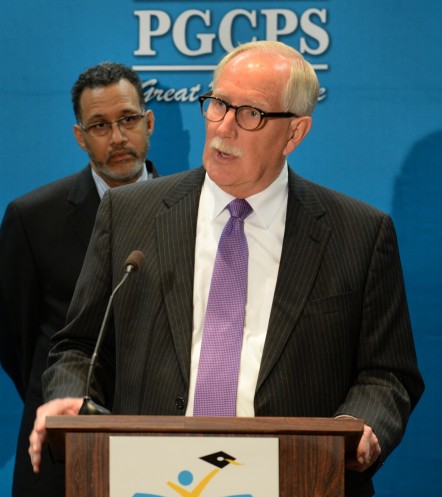

Prince George’s County schools chief Kevin Maxwell, right, has called allegations of systemic corruption baseless and politically motivated. (Mark Gail/For The Washington Post)

As Maryland orders an investigation into whether grades were manipulated to drive up graduation rates in Prince George’s County, employees at several of the district’s high schools say they have encountered signs of grade tampering and pressure to pass their students.

Eight employees, based in six of the county’s 22 high schools, described in interviews with The Washington Post grading incidents they found troubling after allegations emerged of corruption in the school system. Gov. Larry Hogan (R) asked for an investigation on June 25, and the state board of education voted to pursue it two days later.

Prince George’s school officials deny that they engaged in any effort to fraudulently inflate graduation rates, while those who made the allegations — a minority bloc on the 14-member county school board — say dozens of whistleblowers have come forward with evidence.

Employees interviewed on the issue agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity, saying they feared retaliation for speaking out. Several told of being thwarted if they tried to fail a student, which they described as part of a larger push to raise on-time graduation rates.

“It’s a problem we’ve been dealing with a few years now, but it has definitely gotten worse,” one teacher said.

[Maryland officials vote to conduct investigation of graduation rates in Prince George’s County]

Kevin Maxwell, chief executive of the school system, has called allegations of systemic corruption baseless and politically motivated. He and the school board’s majority said they welcomed a state-ordered review, saying it would put the issue to rest.

Maxwell has pointed to an earlier state investigation of graduation rates as evidence that the district does not have a problem. But critics have said that examination was not sufficiently impartial or broad, largely relying on several hours of interviews with Maxwell and four people he had a hand in selecting.

As the debate has intensified, some educators and other employees offered glimpses of what they see as the problem.

One said he did everything he could this year to help a senior headed toward failure — contacting parents, alerting a counselor and an administrator and referring him to a school intervention team. But little changed, so the teenager got an E — a failing grade — in an English course required for graduation.

A couple weeks later, he said, he spotted the student in a cap and gown, collecting a diploma. How that happened remains a mystery, he said. “It solidified what I’d heard about grades being changed and that administrators will do whatever it takes to make sure they meet their graduation rates,” he said.

At another school, a teacher said two of her seniors this year missed weeks of school, did not do assignments or make up work, and failed her course. But the principal encouraged students and their families to appeal, she said, and their course grades were revised to a C and a D. She was told both graduated.

“For a child not to come to class — maybe been in class three days in a whole quarter — and you’re going to change their grade?” she asked. “It’s not right. If they don’t come to school, and they don’t do the work, they deserve to fail. It doesn’t help them.”

The teacher said she believes such appeals and “recovery packets” of work are “a front” for grading changes that allow students to graduate. She said the focus is not only seniors: “They do it for freshmen, sophomores and juniors.” In all, she estimated grades were changed improperly for more than 10 of her students during the past few years.

At a third high school, an employee with firsthand knowledge said grade-change forms are often signed by the principal but not by teachers. The employee said the forms are often attached to academic “packets” designed to compensate for missed or failed work, but many of the packets are only partly complete.

“I think it’s all a numbers game,” the employee said, alleging that more than 100 students at the school graduated with the help of such changes during the past four years.

Four-year graduation rates in Prince George’s have jumped from 74.1 percent in 2013 to 81.4 percent in 2016 — lower than the state average of 87.6 percent but the largest gain for that period of any school system in Maryland.

Maxwell has pointed to the progress as a signature accomplishment since he was hired as schools chief in 2013.

In February, he and other top administrators did a bus tour of the eight county high schools with a graduation rate of 90 percent or better. Students and staff cheered their success, with banners celebrating them as part of the “90 Percent Club.”

Two years earlier, no Prince George’s high school was at 90 percent.

School system officials said they could not comment on questions employees raised about grades without knowing names of the students involved. But they said graduation rates have climbed in recent years as a result of several efforts.

The district has worked with high school principals to set targets for graduation rates, with increases of three to five percentage points over three years, officials said. They said the numbers are goals, with no penalties or bonuses involved.

[Four school board members in Pr. George’s County allege fraud in graduation rates]

They also said student support and intervention have been improved through early-warning systems that identify those at risk and a credit recovery program that gives failing students another chance at learning and boosting their grades so they can stay on track.

One teacher at a 90-percent school said that the day Maxwell and others arrived at her school, she and some of her colleagues rolled their eyes.

“We knew that it wasn’t real,” she said. “It’s just common knowledge that they push kids through who shouldn’t be pushed through.” She said she worries about the message to younger siblings and students who show up and try hard. “Why should they continue to work hard?” she asked. “Why should they come to school and listen to their teachers about putting in maximum effort when you don’t have to?”

Another longtime teacher said that in a couple of cases, students have let her know they passed her class when she knew they failed. She had not signed a grade-change form, she said. “It’s appalling to me,” she said. “I’m not averse to helping a student pass. But when people are pressuring you to do it, when it happens behind your back, that’s when it’s problematic.”

At another county high school, a teacher said she once returned from a three-day leave that fell at the end of a marking period to find that all of her students with failing grades had been given 80 percent for the quarter. That was the threshold for a B, which she said they did not deserve. She said she complained, to no avail. She said tampering needs to stop.

“Kids deserve to get educated,” she said. “You don’t give someone a grade they didn’t earn.”

Prince George’s high school principals disputed allegations of improper practices, saying schools succeed for reasons including a “laserlike focus” on ninth-grade promotion rates and graduation rates, and programs that give learners a second chance to master content and earn credit.

“There’s nothing magical about our methods and no shortcuts to our success,” they said in a recent statement, voicing dismay that at a time of positive momentum, the school system was “again a casualty of unfair, ugly scrutiny.”

The credit recovery program in Prince George’s, expanded and standardized two to three years ago, is one focus of scrutiny. Some students may do “packets” of work aligned to their course that can provide extra points on a quarter grade. Another option involves lessons that are largely online, said special projects officer Janice Briscoe.

Maxwell has said that a majority of Maryland school systems have credit recovery programs, and that the district’s efforts intend to provide students “multiple pathways” to succeeding in school.

[Maryland graduation rates hit new high, with big rise for Prince George’s]

At DuVal High School, a recent email The Post obtained shows that 14 days before graduation this year, more than 140 seniors still needed “one last intervention.”

“If there is any last minute, (rub a genie in a bottle), assistance you can help our future scholars, please assist, (yes, one more time)!” a counselor wrote.

Some saw the email as a sign of pressure to alter grades.

A school district spokeswoman said the email was sent by a member of DuVal’s staff, intending to make sure credit recovery options had been offered to students.

Some parents have voiced concerns, too.

Vida Kelly of Lanham, a DuVal mother, said it’s important that students do the work and come away with a solid education.

“Something is going on, and our kids are on the losing end,” she said. “My prayer is that with all of this exposure, it changes things for the betterment of our children. They’re there to learn, not to just be given grades and pushed along.”

Via Washington Post

Maryland State Board of Education voted to have a Third party to investigate allegations of grade fixing at county schools

***

***